- Home

- India Hicks

India Remembered

India Remembered Read online

MORE GREAT PAVILION TITLES

www.anovabooks.com

On New Year's Day 1947 Lord Mountbatten was summoned to Downing Street to discover his future role in history – to guide India to independence as the last Viceroy. Travelling from post-war Britain under rationing to the outsized splendour of Viceroy's House in New Delhi, the Mountbattens leapt straight into their responsibilities. Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah, Patel, Baldev Singh and a wealth of Marahajas all appear in this testament to the biggest challenge faced by a Viceroy – to break the deadlock that existed between the Indian politicians, to try to avert civil war and to achieve an honourable exit for the British. The result was the creation of India and Pakistan on 15th August 1947.

Lord Mountbatten's seventeen-year old daughter, Pamela, was taken out of school to accompany her parents to India, and spent the next 15 months recording the birth of two nations alongside her own transition to adulthood. Beside her mother, Edwina, this young woman took on far more responsibility than would normally be required of a girl just finding her feet in the adult world. As an eye-witness, Pamela describes often harrowing scenes, colourful and exotic characters and major historic events, as well as wonderful recollections of her trips around India.

India Remembered is a pure evocation of this key period of India and Pakistan's history. Using diary entries and extracts from the meticulously kept family photo albums as documentary evidence, this book is a brilliantly informative read and a chance to witness first hand a generation of characters whose actions were to change the fate of two nations.

Pamela Mountbatten is the younger daughter of Lord Mountbatten, who was appointed the Last Viceroy of India in 1947. At the age of seventeen she travelled to India with her mother and father, witnessing and playing her role in the dramatic events of India's hard-fought independence and subsequent partition. She married the designer, the late David Hicks, and now lives in Oxfordshire in the home they shared together.

India Hicks is the granddaughter of the Last Viceroy of India and daughter of Pamela Mountbatten and David Hicks. Having worked as a model around the world, india is now the author of two books, Island Life and Island Beauty and is a creative partner for Crabtree and Evelyn.

India

Remembered

My parents with Nehru on an elephant proceeding to the Mela.

17th May 1948: My father driving my mother, myself and Nehru on the Tibet Road from Mashobra.

India

Remembered

Pamela Mountbatten

Foreword by India Hicks

Contents

Foreword

by India Hicks

Introduction

by Pamela Mountbatten

The Last Viceroy of India

Map of India Pre-partition

First Impressions

A Huge Task

A Brief Respite

The Mountbatten Plan

Rising Tensions

The Transfer of Power

The First Governor-General of India

Map of India Post-partition

Riots and Refugees

Tours Part I

Gandhi’s Assassination

Tours Part II

Departure

Epilogue

Key Figures

Glossary

Index

Acknowledgements

The Mountbatten Family Tree

Foreword

by India Hicks

I have led by all accounts an unusual life, coming from an unusual family, carrying with me an unusual name. But my unusual life pales in comparison to that of my mother’s. I implored her to tell this extraordinary tale, exactly sixty years later.

I never knew my grandmother, but I clearly remember being told that once after a dinner party in India many years after Independence she was asked who she had sat next to. She replied that he had been a most amusing dinner guest, and when asked if he had been black or white, she simply could not remember.

I knew my grandfather; he was the backbone to our lives. I remember small ‘tasks’ he would set me, standing tiptoed on a chair pushing his shoulders back hard against a stone wall ‘harder child, harder’ he would yell; or tickling a blade of grass across his upper lip as he snoozed in the afternoon, ‘softer child, softer’. He was the indominatable yet gentle giant, until one sunny August day in Ireland the clouds descended on that childhood forever.

It is hard for me to imagine my grandfather, only a few years older than I am now, being asked to dismantle an empire. Unimaginable the responsibility of stemming the tide of violence and controlling cities that were committing suicide. It is not hard, however, to imagine that from the moment my grandparents arrived, they rejected all the Raj stereotypes and looked towards the job with open minds. It is also understandable that, despite his royal ties, my grandfather was a tough-minded realist, committed to those liberal principles which made him acceptable to Atlee’s Labour party. Gandhi, the soft-voiced archangel of India’s independence, sensed my grandfather’s warmth and responded to it, as he had been unable to do with any previous Viceroy.

Criticism over the damnable haste in bringing British rule to an end has never softened. The blunt fact is that no one foresaw the magnitude of the horrors that lay in wait, and their failure to do so would baffle historians in later years. Nehru and Jinnah each made the grave error of underestimating the communal passions which would inflame the masses of their subcontinent, but it was the relative newcomer in their midst, the Viceroy, who took the blame from the rest of the world.

I have travelled my way around this great country, whose name I so proudly carry, staying in youth hostels, occasionally sickened by the unexpected glimpse of India’s timeless miseries or staying in Government houses of considerable magnitude, lavished upon by luxury. Never once during my numerous visits have I ever encountered an Indian within India who, on discovering who my grandparents were, had any other reaction than to smile from ear to ear and beam in fond remembrance as at an old friend, which is how a generation seems to have regarded them.

My grandparents were successful in moving a country in flames forward, and it was an immense personal tribute to my grandfather to accept Congress’s invitation to become the first Governor-General of the Dominion.

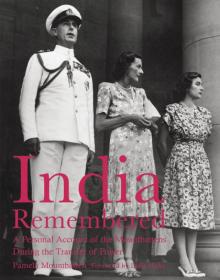

India (left) with her grandfather, Louis Mountbatten, and a family friend.

Aged 17 in the Moghul Gardens at Viceroy’s House.

Introduction

by Pamela Mountbatten

I certainly never planned to write about the time I spent in India with my parents when my father was Viceroy, but I was finally persuaded by my youngest daughter – anything for a quiet life. But then again, I find myself pushed into doing all sorts of things I never intended. My daughter India is very, very determined, encouraging me to go riding in Patagonia, undertake safaris and exotic travel, which I had never thought to go on, but which proved unforgettable in her company. On one occasion, however, she did become over-enthusiastic. She telephoned me from New Zealand to say that she had just booked my seventieth birthday present. I was to go hang gliding: ‘You’ll love it, Mum. It’s thrilling and you’ll only have to run five paces to take off.’ I panicked and flatly refused to go. She took me swimming with dolphins instead.

This project is the result of another of her persuasive assaults. At first I simply handed over the diary I began as a seventeen-year-old. Then we went to look in the Broadlands’ Archives at my father’s photograph albums which he had kept meticulously during his time in India. The pages of his most important album are organised by date and event and carefully captioned in his neat handwriting. As we turned the pages together I found myself remembering those extraordinary months with a vividness reawakened after sixty years. India had many

questions and was also overawed by what she saw – an eyewitness account of one of the most momentous events in modern history. When I saw her reaction, I realised that she was right: I should publish my memories of this period. Since that day we have spent many hours together surrounded by letters, typescripts and images, trying to piece together that time again in a book that might be intensely personal but also accessible to a new generation of readers.

The book we have put together combines the photographs my father assembled with my diaries from that period. It brings it alive to read my seventeen-year-old self, so young in many respects and yet mature enough to understand the importance of the events that erupted around us. I have left many of the passages in that girl’s voice, even though time and experience have since afforded me the gift of greater objectivity.

The time-frame of our stay was March 1947 to June 1948. The Indian sub-continent was divided into two independent Dominions, India and Pakistan, in August 1947 and my father was asked to stay on by Nehru for another ten months as Governor-General of India, a great honour. My father always recognised the importance of records and he encouraged me to keep a diary. Of course when things get interesting, one’s diary entries tend to become shorter or dry up all together because life becomes so hectic, but I am grateful for my father’s persuasion now. I wrote in it regularly in the days leading up to partition but then in September and October, when I was working hard as General Rees’s assistant, there was obviously less time to write and the entries are fewer and further between. By the time my sister and her husband had flown out to join us in December and we began to travel (attempting to visit every state and province in the few months before our departure), the diary was often neglected.

The build up to our departure had its equal share of wracked nerves and excitement, as I record on the pages between New Year’s Day and our departure from RAF Northolt on 20th March. My first entry for 1947 sets the tone for the year and a half to come. We were on a family holiday in Switzerland. My parents had been over-working as usual and were just beginning to relax and my newly married sister, Patricia, and her husband John Brabourne were with us. But my father was summoned to a meeting by the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee.

I write in my diary:

Wednesday 1st January

Daddy was suddenly recalled yesterday by the PM to London and consequently our New Year’s party was slightly gloomy and harassed, particularly as everything now is so uncertain. He and Mummy left this morning which really is very sad as at last we were all together.

The ‘together’ here emphasises how special it was to be together as a family. Obviously my parent’s work had meant that we saw very little of them during the war. For children with fathers fighting in the Far East those last three months were very hard. We were surrounded by the euphoria of everyone celebrating peace in Europe and forgetting the intense fighting against the Japanese. My father took the surrender of the Japanese in Singapore on 12th September. But he had to remain to hand over power to the newly independent governments of Burma, Malaya and Indochina, which became Indonesia, and the Dutch East Indies, and to install the nineteen-year-old Ananda as King of Siam. He only returned to London on 30th May 1946, but my parents immediately left on an official visit to Australia.

During the war, when not at boarding school, I lived with my paternal grandmother, who, as a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, was Princess Victoria of Hesse. She married my grandfather Prince Louis of Battenberg. During the Blitz on London, my father persuaded my grandmother to leave Kensington Palace and come to live at Broadlands, our home in Hampshire. She was a royal princess so I had been brought up to curtsey to her and kiss her hand. This was alarming to my school friends who came to stay but she was a fascinating old lady and they were enthralled by her. Life at boarding school during the war was run on simple lines, as were most people’s lives during those austere years. Therefore the New Year holiday of 1946/47 had been anticipated with great excitement.

The diary entry also hints at the other spoke in the works at this time – the fact that everything about my father’s potential new job was so ‘uncertain’. As has been recorded frequently, it is no secret that my father did not want the job of Viceroy. The command to divest England of the last jewel in the Empire, garnered under his great grandmother, was not an easy one to accept. He also knew that it could mean the ruin of what had so far been a glorious career, for India was wracked with political troubles and many before him had failed to forge a straight path towards independence.

The deadline of June 1948 had been set but there was no clear idea as to how to meet that date successfully. My father therefore made his feelings of reluctance known and also threw in some strong provisos, including the use of his old aircraft, a York, which he had used in South East Asia. He also requested a commitment from the board of Admiralty that he might return to the navy when the job was over and, most important of all, what were virtually plenipotentiary powers. He felt that he had to be allowed to act on his own initative without having to refer everything back to Whitehall. And finally, when it looked as though the Prime Minister and the Cabinet might accept all these demands, he went to the King. ‘Bertie,’ he said, ‘they will be sending me out to do an almost impossible job. Think how badly it will reflect on the family if I fail.’ But the King replied, ‘Think how well it will reflect on the family if you succeed,’ and told him he must go. In fact, unknown to us at the time, Nehru himself had put my father’s name forward as a potential candidate in his meetings with Sir Stafford Cripps during the Cripps mission of 1946 when the British Government had become committed to a policy of complete independence for India. My mother recorded in her diary of 17th February, ‘At home all day but constant conferences and long distance calls!’

Following page: My father’s letter to the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee.

Finally all was agreed:

Thursday 20th February

I went with John and Patricia to the House to hear the statement that Daddy was to become Viceroy read by the PM. It was very crowded and before everyone had become very uproarious during Question Time so that it dissolved into complete chaos, Winston demanding why Wavell was to be recalled and Attlee refusing to give further explanations.

Preparation

The following day my mother and I went shopping with her French dressmaker to try to find materials to make up into suitable dresses. We only had four weeks before we were to fly out. There were some beautiful materials, far better than we had been used to during the war. But we did not have enough clothing coupons, even with the small extra allocation that we were allowed, so we had to be very modest in what we bought. It was exciting for me to have anything new. My mother ordered some dresses from Molyneux, including a beautiful embroidered satin evening dress.

My father introduced me to what was to become my new life by teaching me elementary Urdu out of a handbook for Army cadets. My mother arranged for Miss Lankester, who had worked for the All India Women’s Conference, to come and talk to me about the students in India and the various contacts that I might be able to make. Coming from an English boarding school I was woefully ignorant of politics and international affairs. I felt entirely unprepared to go to another country with so many diverse political parties and such profound problems.

My parents had become engaged to be married in India in 1921. My father was an ADC to the Prince of Wales on his tour of the Far East. My mother and father had fallen in love before he left and he persuaded her to visit India, which she longed to see, while he was there with the Prince. She was barely twenty and had no money of her own, so she borrowed enough for the fare and found herself a chaperone from the list of passengers. The Vicereine, Lady Reading, was an old friend of her beloved great aunt and invited her to stay. One evening my father asked the Prince to lend him his private sitting-room in the Viceregal Lodge (now part of the University in old Delhi) and there he asked her to marry him. When she heard they were engaged, the Vicereine

was horrified. She had hoped Edwina would have chosen someone older, ‘with more of a career before him.’

Family Ties

My father’s mother was Princess Victoria of Hesse, who was a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. He was born at Frogmore House, in the Home Park of Windsor Castle, in 1900. He was christened Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas, but very soon became known as Dickie. His elder sister, Princess Alice, married Prince Andrew of Greece and their youngest child, Philip, became the present Duke of Edinburgh.

My paternal grandfather was Prince Louis of Battenberg, who in 1917 became Marquess of Milford Haven when King George V anglicised the royal family names, and our family name was translated into Mountbatten. My grandfather had been forced to resign from his post as First Sea Lord in October 1914, following a hysterical wave of anti-German feeling – he was a German by birth – a humiliation which my father felt had been expunged when he himself became the First Sea Lord in June 1950.

My mother, Edwina, was the daughter of Lord Mount Temple. She and my father were married in 1922. By the time they arrived in India in 1947 as Viceroy and Vicereine my father was forty-six and my mother forty-four. He was enthusiastic, pragmatic, extrovert, a raconteur and fascinated by his family connections, but above all extremely hard-working. She was an introvert, but fearless and excited by action, and bored by protocol and old-fashioned apathetic comfortable society. They worked well as a team; my father had appointed her towards the end of the war to fly into the prisoner of war camps, and report back to him on the conditions. He had a very high opinion of her abilities.

My father trusted her decisions implicitly. For instance, when we met as a family for breakfast, he would simply ask her, ‘What decisions did you make?’ ‘Who did you see?’ And of course, her special relationship with Pandit Nehru was very useful for him – ever the pragmatist – because there were moments towards the end of our time in India when the Kashmir problem was extremely difficult. Pandit Nehru was a Kashmiri himself, so he was emotional about the problem. If things were particularly tricky my father would say to my mother, ‘Do try to get Jawaharlal to see that this is terribly important...’

India Remembered

India Remembered